Museums around the world are always on the look out for new ways of bringing history alive, but nothing could prepare me for what I was to experience at the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocidal crimes in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. No fewer than three survivors of this former Khmer Rouge prison could be found in the grounds and were prepared to share their testimonies of the terrible experiences they encountered.

I met the man who, as a nine year old boy, became an orphan when his parents were taken away from the institution to be killed, the mechanic who endured torture but survived because he repaired typewriters for his guards and the painter who was only spared death because he painted official portraits for the government. They all had harrowing stories to tell, but were happy for visitors to quiz them life under Pol Pol’s brutal regime that ruled the country between 1975 and 1979.

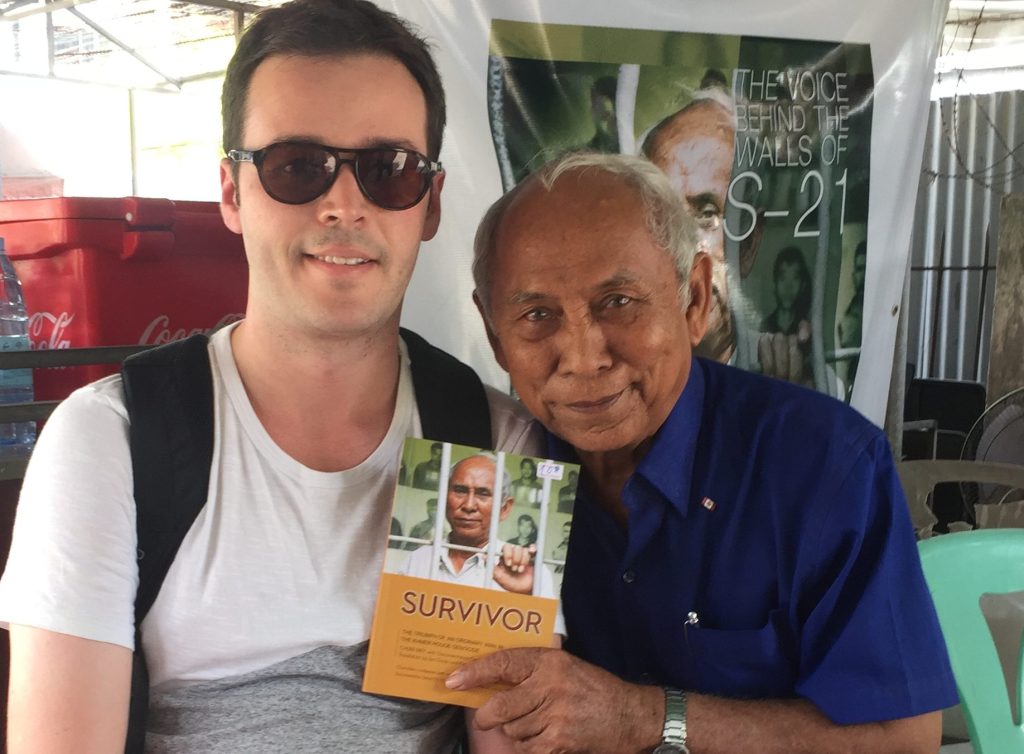

The story of Chum Mey – the mechanic – is quite extraordinary. Orphaned as a child, both his daughters disappeared during the madness of Khmer Rouge rule. He was beaten, had a toe nail was removed and his legs were shackled to the floor. “If we made a sound by moving our legs, and the chains rattled, they would come and give us 200 lashes,” he wrote in a book I bought at the museum. But he does not condemn those who tortured him as they were “not senior leaders they were doing what they had to do at the time” – “How can I say I would have behaved differently?…. Even the ones who tortured me, they also lost parents and family members,” he added.

Formerly Tuol Svay Prey High School, the buildings I visited were taken over by the Khmer Rouge security forces and turned into what became known as S-21, the largest centre of detention and torture in the country, where thousands of people were held and later killed. The classrooms became cells, where prisoners were chained in using shackles inherited from French colonial times so they could not escape. Pots used as toilets were only emptied every two weeks and if any of the contents was spilled, the residents were forced to use their tongues to lick the floor clean.

Tuol Sleng was run by former school teachers who sought to extract confessions of prisoners links to foreign intelligence agencies, including the CIA or KGB. When the prison was discovered by the Vietnamese, who in 1979 invaded the country and in doing so brought an end to Pol Pot’s regime, they found rotting corpses still in shackles and as well as torture implements. In an out building records and thousands of photos of victims were found, many of the latter are on display for visitors today to view.

From S-21 many of the prisoners were taken to an open space where they were executed at what became to be known as the killing fields. Some 343 of these gruesome sites – that the regime told prisoners was to be their “new house” – have been recorded in Cambodia. But many have found new uses, such as for growing rice, and their former use is not marked.

There was however one killing field I was able to visit at Choeung Ek, some 15km from downtown Phnom Penh, where more than 160 mass graves were found (in one containing the bodies of Pol Pot’s own soldiers the corpses were found to have no heads). It’s a poignant place where fragments of bones and items of clothing brought up by the rain can still be seen ingrained in the dirt path. Board walks that provide some protection from walking on the graves are only a recent addition. In the centre of the site, there is a stupa made up of 8,000 human skulls from some of the victims.

Between 17, 000 and 20,000 men, women and children were executed here, usually on the same day they arrived from the prison. Victims were made to kneel down, they were blindfolded and their arms were tied behind their back. They were then struck on the back of their heads with an iron pole, and the bodies rolled forwards into a freshly dug six meter ditch. On so called ‘magic trees’, loud speakers were hung enabling sounds to be played during the process to blot out the moaning.

Executioners had the gruesome job of getting into the mass grave to ensure the victims were actually dead, but to be doubly sure they were then sprayed with a chemical, which had the added benefit of disguising the smell, so passers by would be less aware of what had gone on here.

Revolution in the making

After years of steadily building up support in rural parts of Cambodia, the big break-through for the Khmer Rouge came when they took Phnom Penh, the capital, on 17th April 1975. Over the next three years, eight months and 20 days (Cambodians today describe the term of terror very precisely) an estimated three million people were wiped out as Pol Pot and his followers subjected the population to a brutal and radical restructuring of society.

Entire towns were emptied and their inhabitants marched to rural areas where they were forced, as slaves, to labour for 12 to 15 hours a day. Children aged seven and above were separated from their parents, while husbands and wives were not allowed to show any public signs of affection (marriages themselves were prohibited). People lived in squalid conditions, where disease was rife, and were given meagre portions in communal dining halls, which is why so many people starved to death.

Modern life was quite simply eradicated. Law courts, newspapers, the postal system, overseas communications and money were just some of things that were done away with.

The Khmer Rouge believed that it could bring about a return of Cambodia’s greatness – “more glorious than Angkor” which had ruled a vast empire that peaked in 13th century – through agricultural reform and the creation of large scale cooperatives. Peasant-life became the inspiration for the regime’s attempts to create an egalitarian society free from the corruption that had in the past beset the country, which it re-named Democratic Kampuchea.

But the Khmer Rouge was completely misguided; ideology was more important to them than the practicalities of building a successful nation. Intellectuals were wiped out and the regime neglected to work with anyone who had technical skills – the very people who could help re-build a new Cambodia – unless they were revolutionaries. In addition, a third to a half of the population was too sick or hungry to work at the levels required. Put these factors together and it’s no surprise that co-operatives fell considerably short of the levels that regime hoped.

Pol Pot’s claims at success of everything from finding cures to malaria and eradicating illiteracy were highly inflated; they were little more than talk. In reality, society regressed considerably, with devastating effects. Symbols of the modern world, such as functioning hospitals, were reserved for senior leaders and foreign diplomats. While some buildings in Phnom Penh were maintained, others lay in ruins and the streets became overgrown, while animals roamed free.

Most foreign officials were restricted to their embassies in a tightly defined area where there was a shop selling imported goods (they needed special permission to venture further afield), so wouldn’t have known the full tale of devastation. And the majority of western journalists left Cambodia once it became clear that the Khmer Rouge were about to take the capital.

The 1984 film, the Killing Fields, which was based on a true story, captures the brutality of life under the harsh policies of the Khmer Rouge. New York Times journalist Sydney Schanberg (played by Sam Waterston) was in Cambodia in the dying days of the US-backed administration in Phnom Penh as US bombs were being dropped on innocent civilians. He and his interpreter, Dith Pran (played by Haing S Ngor), were there as the child soldiers of the Khmer Rouge arrived in the capital as happy crowds waved flags in celebration that the old corrupt regime had been overthrown. They stuck around longer than many western journalists.

But the jubilation soon turned to terror as the incoming army executed prisoners in the street and made residents to leave the city. Foreigners who had been enjoying drinks parties on the terrace and splashing around in open air swimming pools were forced to take refuge in embassies while they awaited evacuation. Those without the ‘right’ passport were not so lucky, as was the case with Dith Pran, who was captured by the Kymer Rouge and sent to a re-education camp. There he witnessed first-hand the “killing fields” (a term coined by Pran), where the bodies of victims of the regime were became piled up.

It seems the world now knows – or at least thinks it knows – how evil the Khmer Rouge were in the time they were in power. Just how did this regime, however, get into power? Why were the warning signs (if there were any) missed?

Developing an ideology

Pol Pot, born Saloth Sar in 1925, showed little sign in his early years of the monster-like characteristics that would go on to define him when the brutalities of the Khmer Rouge were in power. After growing up in Prek Sbauv, a small fishing village in Cambodia, and attending a Catholic school in the capital Phnom Penh, Sar moved to Paris to study radio electronics. The student was, according to historian Philip Short (author of an excellent biography of Poll pot), a “soft-spoken, smiling, amiable man” who “was remembered for his sense of fun and good companionship.”

As a teacher, back in his native Cambodia, he was “adored by his pupils”. As a communist, he “was valued for his ability to bring together different tendencies and groups.” Indeed, he referred to himself then as Pouk, which translated to “mattress” – he saw his “role was to soften conflicts.”

Knowing what happened under the brutal rule of the Khmer Rouge, putting the characteristics of the young Sar versus his later self seems a challenging task. What went wrong? How did he – and his compatriots – bring Cambodia and its people to its knees?

The Khmer Rouge may have focused their destruction on Cambodia, but the communist ideas of the movement’s top leaders – including those of Sar – were born in France in the 1950s. Sar, who joined a secret cell called Cercle Marxiste (“Marxist Circle”) in 1951, was one of many students in France who decided that communism offered the best chance of bringing about Cambodia’s independence.

Sar returned to Cambodia in 1951 to find a prosperous country, but at the same time in the grips of civil war. On one side were the Democrats who were in alliance with King Sihanouk, who ruled by decree. While on the opposing side was Khmer Viet Minh which enjoyed the support of the world communists. The students from Paris backed the latter, although they were resentful that it was in reality a Vietnamese movement and not a Cambodian one – something that would become a reoccurring theme in the revolutionary struggle.

Cambodia officially achieved independence from France on November 9th 1953 (although French troops didn’t leave immediately) and the first elections were scheduled for 1955, which it was expected that the Democrats would win by a landslide. But then, shortly before the nation was due to go to the polls, King Sihanouk abdicated – passing the throne to his father – and the vote was delayed.

Sihanouk formed a new political party, which numerous politicians from across the spectrum flocked to, and it was declared winner of the elections. There were reports of corruption and voter intimidation, which both France and the US downplayed in a bid to ensure a right-wing dominated government favourable to its interests was appointed. Cambodia became a one-party state, headed up by its former king.

Vietnam, which at the time were masters of the communist movement in Cambodia, declared that the armed struggle within its neighbouring country was over following. Rather than attempting to overthrow Sihanouk’s government, the focus should just be about fighting American imperialism, it said.

But not everyone was prepared to give up the revolutionary struggle and the communist movement in Cambodia – allied to the party in Vietnam, but also independent of it – was re-built one member at a time. Sihanouk initially turned a blind eye to communist recruitment activity (he actually believed it would become a dominant force in his country in the years ahead, something that perhaps softened his move to become pals with the Khmer Rouge later on). However, the Cambodian communists were restricted to an isolated jungle base in South Vietnam and still felt reliant on the Viet Minh forces.

Cambodia’s revolutionary war was officially launched, albeit with modest beginnings, on January 18th 1968, by Sar, who had become General Secretary of what would become the Communist Party of Kampuchea in 1963. The Khmer Rouge movement had been growing at a rapid rate in the preceding years following bouts of repression by Sihanouk. But, as we shall see, even in 1970 the future of the organisation didn’t look certain as they didn’t even control a fifth of Cambodia.

The events in Cambodia can’t of course be considered in isolation from what was going on in the wider region at the time. At the end of the 1960s, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong were using Cambodian territory as a springboard to launch attacks against South Vietnam. This prompted President Nixon to launch bombing raids in 1969 (which would become so severe that the craters were described as looking like “the valleys of the moon”) as well as a land invasion to the eastern part of the country.

As for Sihanouk, in many ways he had an over-inflated view of himself. He believed the Cambodian people needed him (he had become quite upset when peasants denounced him) and thought he was integral future success of the country. Yet in March 1970, his luck was to run out and while he was abroad he was informed that he had been removed as Prime Minster by a coup launched by General Lon Nol. The US had found Sihanouk unpredictable to say the least over the years (he had told the US he didn’t need their aid any more in 1963 and then in 1965 turned his lot to China), so weren’t sad to see him go.

Sihanouk took up residence in Beijing and formed a government-in-exile, before later forming ties with the Khmer Rouge. He lived a lavish lifestyle, a long way from the peasant lifestyle that the aspiring Cambodian government aimed to create, but his involvement with the organisation would go on to help give it the international clout it needed. Sihanouk was later given a palatial home in Pyongyang by North Korea.

The prince returned to Phnom Penh in September 1975 and initially lived the high-life, enjoying foie gras and fine wines at Royal Palace. He embarked on a world tour, where he defended the Khmer Rouge regime. But back in Cambodia, Sihanouk soon discovered the new realties of life. “My people…. had been transformed into cattle… My eyes were opened to a madness which neither I nor anyone else had imagined,” he later said as he toured the country. Sihanouk stepped down – on what he said were health grounds – in April 1976, a move which would allow him a position in the future in Cambodia. His family returned from exile in China 1991 and he was re-crowned in 1993.

Turning point

How communism was played out in Cambodia was always going to be different from China or neighbouring Vietnam. As Sar himself said, it had been given a “Buddhist tincture” and wasn’t going to simply swallow the writing of Marx of other leading thinkers. In Cambodia, Rural peasant farmers would in many ways be the symbol of the revolution.

As the movement built up support in the 1960s, the Khmer Rouge seemed careful not to antagonise the people it wanted to win over. The US Defence Intelligence Agency noted that “on the whole [Khmer communist cadres] have attempted to avoid acts which might alienate the population, and the behaviour of Vietnamese communist soldiers has generally been exemplary…”.

No-one could be truly prepared for the horrors that would later follow.

In 1970 Sah announced he was changing his name to Pol (he later called himself Pol Pot, meaning ‘political potential’) and also gave aliases to other senior figures. “It was a rite of passage, opening the way from one existence to another,” wrote Short. “Khmer men took new ‘names-in-religion’ when they became monks; Khmer Rouges did so when they took on new responsibilities.”

But it has been said than the Kymer Rouge movement only really took off after the Prince persuaded his subjects – following his removal from government in the 1970 coup – to join the movement. It of course also helped that since the 1950s Sihanouk had been developing ties with the Beijing.

Then, in 1972, the Khmer Rouge changed its policy to promote a complete re-fashioning of Cambodian society. Families were forced out of their homes, which were burned down so they could not return, and moved to join co-operatives where they were made to farm the land with others. By November 1973, a US consular office was able to report “deserted villages, empty roads, abandoned rice fields and abandoned towns…” The account added:

“Conditions in the new locations are reportedly not good. [Those] who have escaped say they are crowded, dirty places where people suffer from lack of food and [there is] a great deal of sickness…. All land is organised and worked in common… and even though production has increased through use of fertilisers and other scientific methods, people are [said to be] unhappy because they are forced to work constantly and do not have land of their own.”

The Khmer Rouge’s intention was to “build a clean, honest society,” where everyone was equal and people didn’t profit by selling to government-held areas. But Pol Pot also justified the policy on practical grounds of ensuring continuity of food supplies for the army, particularly in areas where a large proportion of men had gone off to fight. And he claimed that the majority were “content with and faithful to the new collective system. To back-up this claim Pol Pol also later said that 75% of the population had been virtually destitute before.

Could this really be justified as progress?

For the US and Lon Nol’s regime, the writing was on the wall. Kissinger thought initially it may have been possible to do a deal with Sihanouk, but later acknowledged that after mid 1973 he believed Cambodia was unwinable. Lon Nol’s troops suffered from “chronic deficiencies of poor leadership, corruption, inadequate training and poor morale,” a US military historian would later write.

What is however interesting is how clueless the US were aware about the power of the Khmer Rouge. They thought that the organisation was backed by the Viet Cong. In reality, the Khmer Rouge hated Vietnam which it saw as the enemy. The US’s understanding and interest in the regime improved little once it took Phnom Penh. They just saw it as a side-show of the war being fought in Vietnam.

Chaos

After Phnom Penh was taken by the Kymer Rouge on 17th April 1975, some of the elite weren’t initially worried and thought that life would carry on for them as before. Even Lon Nol, who was among those on a list of people on the government side to be executed, didn’t choose to flee immediately. “Some of those people are my friends”, said a senior engineer in the recently disposed government of the Kymer Rouge. “They’re patriots first and communists second. They will abide by the will of the people.”

But the tide quickly turned as the inhabitants got a closer look at the peasant soldiers who were “covered in jungle grime, wearing ill-fitting black pyjama uniforms with colourful headbands or peaked Mao caps,” according to one eye witness. They “didn’t smile” and “looked from a different world.”

It was these new arrivals, the “poorest of the poor,” who “became the model for all of the rest,” said Short. “Those from the better-off regions, who joined the revolution later and in time made up the vast majority of the Khmer Rouge soldiery, were pressed into the same mould.” Many were nothing more than teenagers and they were not used to city life – they drank from toilet bowls, they tried to eat toothpaste and even consumed engine oil. Hospitals were abandoned and the National Bank was blown up, probably after being looted for gold.

The Kymer Rouge ordered for everyone to be evacuated from their homes in Phnom Penh, partly so students and intellectuals would be “extricated from the filth of imperialist culture” and so “the system of property and material goods… could be swept away.” Short described the operation as “a shambles”: ” To move two and a half million people out of a crowded metropolis at a few hours’ notice, with nowhere from them to stay, no medical care, no government transport and little or nothing to eat, was to invite human suffering on a colossal scale.”

One eyewitness account – published by Short – recorded the carnage: “Sick people were left at the roadside. Others were killed [by the soldiers] because they could walk no further. Children who had lost their parents cried out in tears, looking for them. The dead were abandoned, covered in flies, sometimes with a piece of cloth over them…”

Some evacuees tried to carry with them everything from their old elite lives – everything from televisions to grand pianos. If the possessions were not confiscated by (mostly unfriendly) soldiers, they would soon find that these items useless once they arrived in primitive rural villages. What good would electrical items when there was no electricity? They were very unprepared for what was to come.

Could things have been different? Most people were completely fed up with Lon Nol’s administration by April 1975, so would have been “ready and willing to support virtually any policy the new regime chose to introduce,” said Short. While many leaders would have opted national reconciliation, Pol Pot had different ideas: “To him, the city-dwellers and the peasants who had fled to join them in the dying months of the war were ipso facto collaborators who had to be dealt with as such.”

Building a new nation

“Agriculture is the key both to nation-building and to national defence,” announced Pol Pot, who wanted to double or triple the population size to 15 or 20 million people within 10 years. In order to the country to “make quick progress” and not have to rely on foreign imports (which he didn’t completely rule out, but seemed to discouraged) he wanted to achieve 70 to 80 per cent farm mechanisation in five to ten years, as well as re-building industry.

Pol Pot’s promise to invest in rural Cambodia – and in particular irrigation to bring water required for rice production – did win over some Western critics, including the charity Oxfam. After all, other policies had in recent years failed to improve the lives of ordinary people. The problem, however, was how it was implemented and Cambodia became, according to Short, a “slave state, the first in modern times”:

“Pol enslaved the Cambodian people literally, by incarcerating them within a social and political structure, a ‘prison without walls,’ as refugees would later call it, where they were required to executed without payment whatever worked was assigned to them…. failing which they risked punishment ranging from the withholding of rations to death.”

“No other communist party – whether in China, Vietnam or North Korea – has gone so far in its attempts directly to remould the minds of its members,” wrote Short. “Under Pol’s leadership, the CPK was unique in its determination to create a ‘new communist man’ by pushing the logic of egalitarianism, co-operative self-management and the withering away of the state to its upper limits.”

Even China’s communist regime, which had been no stranger to brutal policies imposed on its people, seemed to urge caution on Pol Pot on over stretching its radical road to socialism. But Beijing wasn’t however about to abandon its long-standing ally, quite the opposite in fact. It provided food aid did, military supplies (including rockets used in the terrifying siege of Phnom Penh), as well as paying for factories to be renovated and offered technical training.

For China, Pol Pot’s Cambodia stood apart from Vietnam where the Soviets were dominant. Having Beijing as an ally suited the Khmer Rouge because, although they were on the whole cordial with Hanoi, they did think that it would become a strong opponent. Pol Pot’s strategy, which China supported, was for Cambodia to buy time before it could hold its own. But for Phnom Penh at least, time was something that was in short supply.

‘Liberation’

Pol Pot frequently saw the enemy as Vietnam and it turned out that he was right to fear them. While Vietnam and Cambodia had been rivals for some time, the two sides had attempted to maintain cordial relations. But as early as December 1976 Pol Pot had ordered for a longer “long-term preparations both for a guerrilla war and warfare using conventional forces” to be made and military bases to be readied.

But then, as the latter stepped up anti-Vietnamese purges, Vietnam began bombing raids along the Cambodian border and things escalated from there to a full scale invasion on Christmas Day 1978. Finally, On 7th January 1979 Vietnam “liberated” Phnom Penh which had been abandoned by the country’s ill-prepared leaders. Two days earlier Pol Pot had only said on his radio broadcast there were “temporary difficulties” (the “valiant and invincible Cambodian army” were winning, he said).

The new Vietnamese-installed government was made up of a number of former Khmer Rouge officers, including current prime minister Hun Sen (who had defected to Vietnam in 1977). And the Vietnamisation of Cambodia followed, with representatives of Vietnam in every government department, while schools were made to display pictures of Ho Chi Minh and Stalin.

Vietnam may have taken Phnom Penh, but the invading army had little hold over rural areas and so the Khmer Rouge hung on to power there, thanks to support from the likes of China, the US and Thailand. The former in particular wanted to make Vietnam bleed given that it was backed by the Soviets who at the time were re-affirming their ambition for global expansion given their invasion of Afghanistan in 1979.

The Khmer Rouge realised it needed to some extent amend its ways if it was to have any longevity; changes included no longer enforcing collective eating to allowing families to live together again. Even the Communist Party of Kampuchea announced its self-dissolution in December 1979, allegedly so it could fight with other nationalists to remove the occupiers. But dispensing with the word ‘communist’ (and saying they no longer believed in prioritising socialism) would have no doubt appeased the Khmer Rouge’s capitalist backers in the West (and meant they kept their seat at the UN).

Pol Pot and his followers were also helped by the fact that Vietnam attempted to ship factory equipment and rice stockpiles out of Cambodia. Humanitarian aid was also stolen and many Cambodians returning to cities found their homes occupied by Vietnamese natives. Any good will that Vietnam had won from the people was lost by removing the Khmer Rouge regime from Phnom Penh was lost.

Although ordinary people were starving after the Cambodian capital fell in 1979 (and it is said that 650,000 people died in the year, not least due to he disease-ridden condition Thai camps), there was no sign to many visitors that the Khmer Rouge was struggling for funds, as an account by the New York Times journalist, Henry Kamm demonstrates:

“The Khmer Rouge guest house was the very latest in jungle luxury. It was clearly modelled on the sumptuous hunting lodges to which the French planters of the past invited guests for weekend shoots…. Plates of fruit brought from Bangkok were renewed each day. The best Thai beer, Johnny Walker Black Label scotch, American soft drinks and Thai bottled water was served.”

All remaining Vietnamese soldiers finally left Cambodia in 1989, the same year that the Berlin Wall fell in Europe. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union (it had in fact stopped funding Vietnam when Gorbachev came to power in 1985), the Cold War was effectively ended and the US saw no need to back Cambodia as a rival to Vietnam. Pol thought at one stage he could re-take Phnom Penh, but he settled for the provincial capital of Pailin (an area rich with mines).

In 1990, the US ended its support for Pol Pot and its followers, while China also said it was cutting aid to them and normalising relations with Vietnam. The Khmer Rouge was a signatory of the 1991 Paris Peace Accords, which installed a UN transitional government for a two-year term. But it boycotted the elections that followed in 1993 and continued to wage a guerrilla war from the western jungle.

Had it decided to fight in the 1993 election when it was still in a relatively strong position, things could worked out differently for the Khmer Rouge. In the end it grew weaker and weaker, and in its latter years was forced to frequently move bases. Only later did the movement think it should switch to fighting at the ballot box, but it was too late. The Khmer Rouge was not officially defeated until 1999, the year after Pol Pol died (having evaded justice), when the last guerrilla officer was captured.

But was that really the end of the Khmer Rouge? Hu Sen, the authoritarian leader of Cambodia, former Khmer Rouge politician has, along with Chea Sim, the President of the Senate, been described as “utterly merciless and ruthless, without humane feelings.” And its said that given the make-up of the current government that it protects former Khmer Rouge leaders who stand accused of crimes against humanity.

Next week: The legacy of the Khmer Rouge in modern Cambodia